Click to enlarge.

The 2 November meeting of the Civil War Round Table of Greater Kingston featured Paul Van Nest, who spoke to us about the First Battle of Manassas.

On 15 April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 three month volunteers for the United States army. By mid July of that year, the first of these volunteers were nearing the end of their term of enlistment and there had not yet been a decisive engagement. The Federal government decided to force an engagement with its enemy in Virginia just south of Washington.

Northern Virginia was very poor, backwoods territory. It was mainly scrubland interspersed with a few farmers' fields . The roads were poor, and were not at all suitable for large troop movements southwards. But this was the route chosen by the U.S. War Department. A large Federal army left from the District of Columbia and entered Virginia via Alexandria.

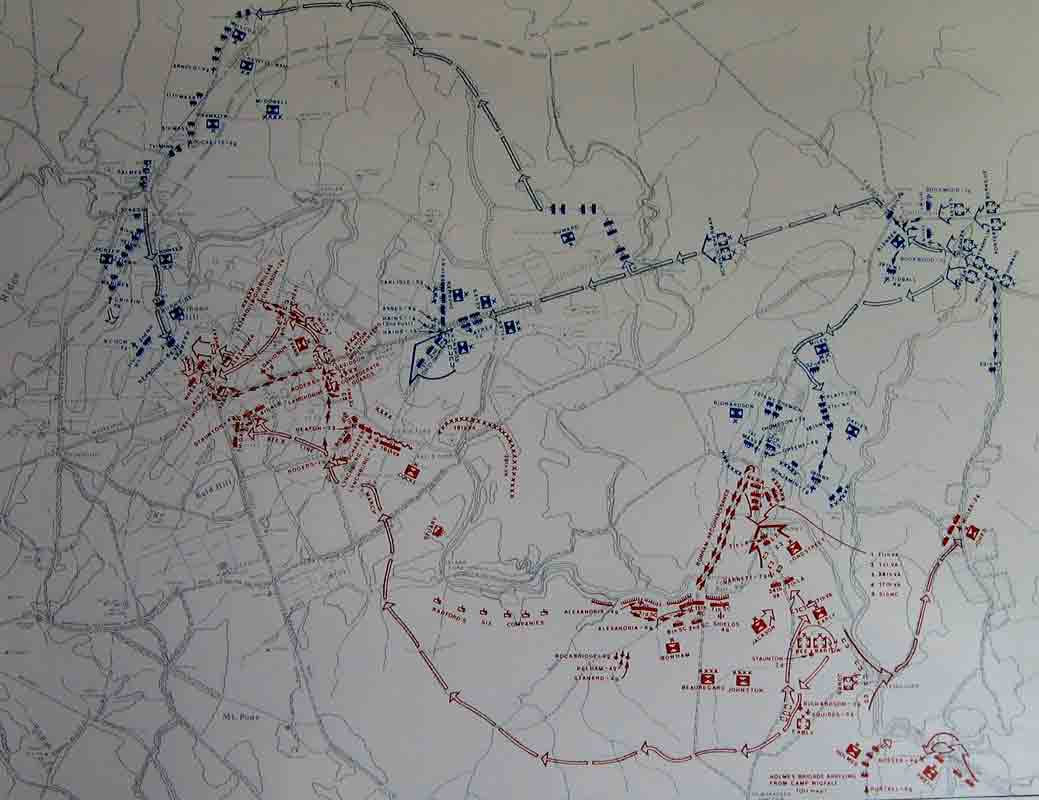

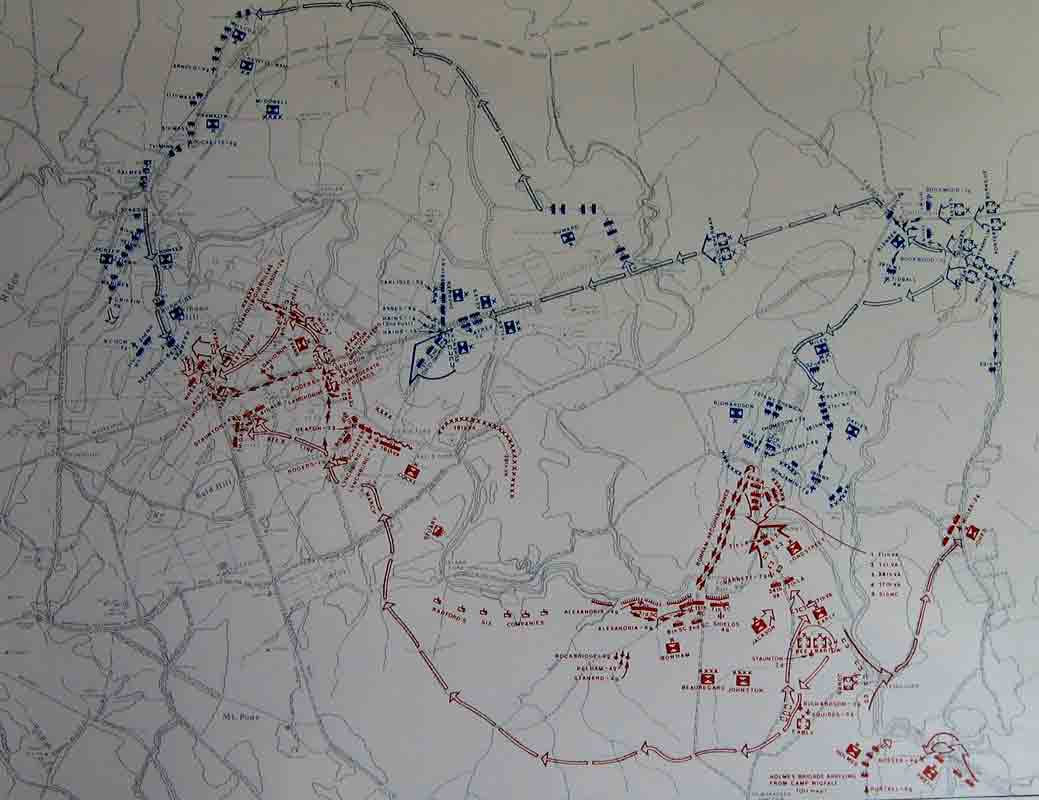

The Federal objective was Manassas Junction, a town one mile east of the junction of two important rail lines, the Manassas Gap Railroad and the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. The Confederates decided to defend this strategic objective at the fords of the Bull Run Creek.

The Confederate armies were commanded by Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard with seven brigades, and Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston with four brigades, one of which was commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Jackson. The former defended the Junction; the latter faced Gen. Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley. These two forces totalled 32,000 men if the units could all be brought together.

The Federal army was led by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell and comprised 35,000 men in five divisions. The numeric advantage was not as telling as the Federal side would have hoped. Many of McDowell's men were volunteers nearing the end of their service. The Union army would be forced to attack; the Confederates would have the easier task, especially with inexperienced troops, of preparing their defences in advance and wait for their enemy to engage. The attacking army would have to march its men to the battleground against a rested and prepared enemy with short, interior lines of communication and supply. The Federals, on the other hand, would have to maintain and defend extended lines of communication and supply, stretched out over poor roads and unfamiliar hostile territory.

The Federal army marched out of Washington at noon on 16 July, 1861. They prepared for battle at Fairfax Court House, but the Confederate force there withdrew before the larger Federal force and there was only a rear guard action. The Union vanguard advanced towards Manassas Junction and made clear that the rail junction was their objective. When Richardson, under Tyler, tried to force his way across Bull Run creek on afternoon of 18 July, his troops were repulsed by Longstreet's men in what became known as the Battle of Blackburn's Ford.

As the large Federal army drew up around Centreville, water and food became critical. The city wagons his army used broke down on the rough tracks and civilian teamsters became lost and scattered. McDowell would have to take a whole day to resupply his army: Friday, 19 July. He also took this day and the next to determine his plan of attack. Battle orders were issued after dark on 20 July. The battle was to commence the next morning.

The Confederates had not wasted the time McDowell had given them to prepare for battle. Johnston's army was 60 miles away at Winchester, facing a Federal force of 18,000 under Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson. Most of Patterson's men were at the end of their enlistment and refused to fight to keep Johnston in the valley. Johnston began to withdraw his army from Winchester at noon on the 18 of July, crossed the Shenandoah Valley and the Blue Ridge Mountains, and arrived at the railhead of Piedmont, Virginia. Here was a single track railway that ran to Manassas Junction. Johnston ferried his troops in successive trips down this line, a seven hour ride (4 mi/h). The majority of his troops arrived at Manassas Junction the day before the battle. More troops arrived from Richmond. McDowell had given his enemy just enough time to be at full strength for battle.

The Federal advance was supposed to commence at 2:30 AM on 21 July but a huge traffic jam developed at Cub Run Bridge. McDowell was incapacitated with food poisoning and was late in clearing the mess. The first shots were fired at 6:10AM by the Federal's 30-pound Parrott.

The Union attack plan was to demonstrate in front of the enemy, while moving a large force on a ten mile march around to their left flank to attack by surprise. Unfortunately, this force was spotted at a great distance by Alexander Porter. The Confederates had a flag/lantern semaphore system and alerted Evans on the Warrenton Turnpike of the perceived threat on his flank. Evans left only a token force to deal with Tyler's feint and led the 1st Louisiana Tigers and 4th South Carolina to deal with the new threat. Simultaneously, Burnside's 2nd Rhode Island occupied the high ground and the Confederates attacked.

The Federal troops following Burnside were supposed to be joined by units following via a shorter route, but they had also taken the long way around. They arrived not only late but also fatigued, giving the Confederate brigades of Bee and Bartow time to reach the field and reinforce Evan's 2 regiments. By noon, Union forces overpowered these Confederates and they retreated up Henry House Hill where Jackson's brigade with Hampton's Legion had just formed.

A two hour hiatus ensue in which Federals got into position while Confederate reinforcements reinforced Jackson's line. At 2 p.m., the battle recommenced with McDowell ordering two batteries up Henry House Hill. This left the Federal commanders scrambling to get supporting troops up to protect the guns. Confederate and Federal units attacked and counter-attacked for two hours across these fields. There was a great deal of confusion on the battlefield and, amidst the smoke and confusion of uniforms and flags, many soldiers on both sides fell victim to friendly fire. By 4:00 the Confederates held the guns and the fighting swung west to Chinn Ridge. Howard led the last of McDowell's brigades on this flank, but Early's and Elzy's brigades arrived in time to drive Howard off the ridge. McDowell then ordered a retreat and the troops returned to Centreville the same route they had used that morning, despite the knowledge of all the short cuts now available to them - inexperienced staff work once again!

By 10 PM, most of the Federal army had retreated to the area around Centreville and fell asleep on their arms. However, the Federal army was now badly exposed in hostile territory. McDowell's officers agreed that a general retreat back to Washington should commence immediately. The soldiers were awakened and forced to march all night along those same rough roads. For most of these men, it was the worst night of their lives.

The Federal government had hoped to draw the Confederates into battle and defeat their army in a quick, decisive fashion. That did not happen. The North was not broken, but was now resolved to a long war ahead. On the other hand, the successful defence of Manassas Junction was both in fact and psychologically a victory for the Confederates, and they were lulled into a false sense of security in their armies.

The actual casualties were not heavy by the standards of upcoming battles. It is difficult to determine actual losses, but the best guess is that the Federal forces suffered about 8% casualties, and the Confederate forces around 6%. By comparison, in the Mexican War, the U.S. had lost 1733 men; half that number had been killed in just one day at Manassas. It was the first major engagement of the war, and left all participants and observers with a clearer view of what the near future would bring.

-- Carl Kaduck